“Yule Tidings”

Season 1, Episode 4

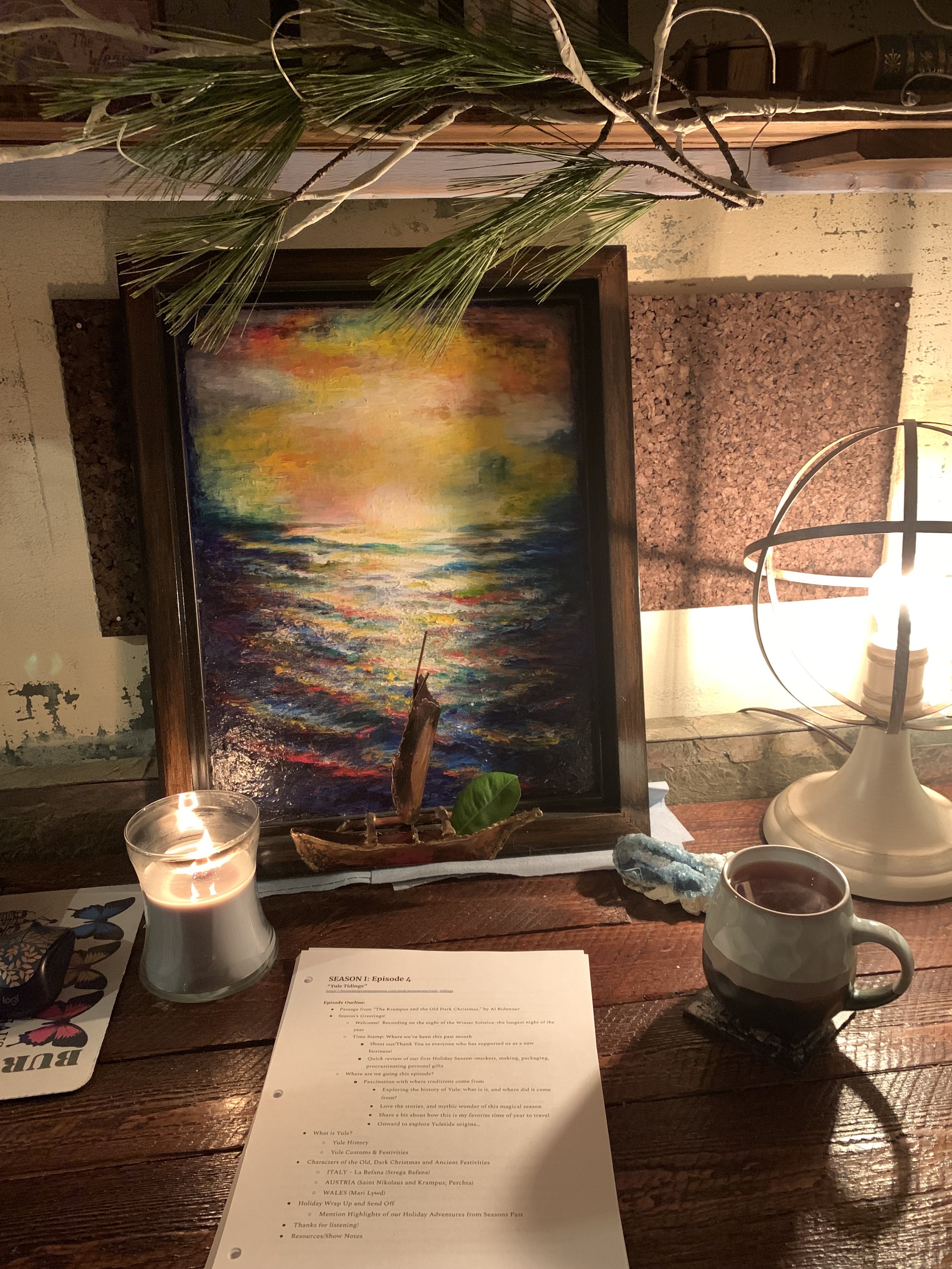

Travel Photography from our trip to Vienna, where the Grumpy Gnome found his merry kin…

Episode Outline:

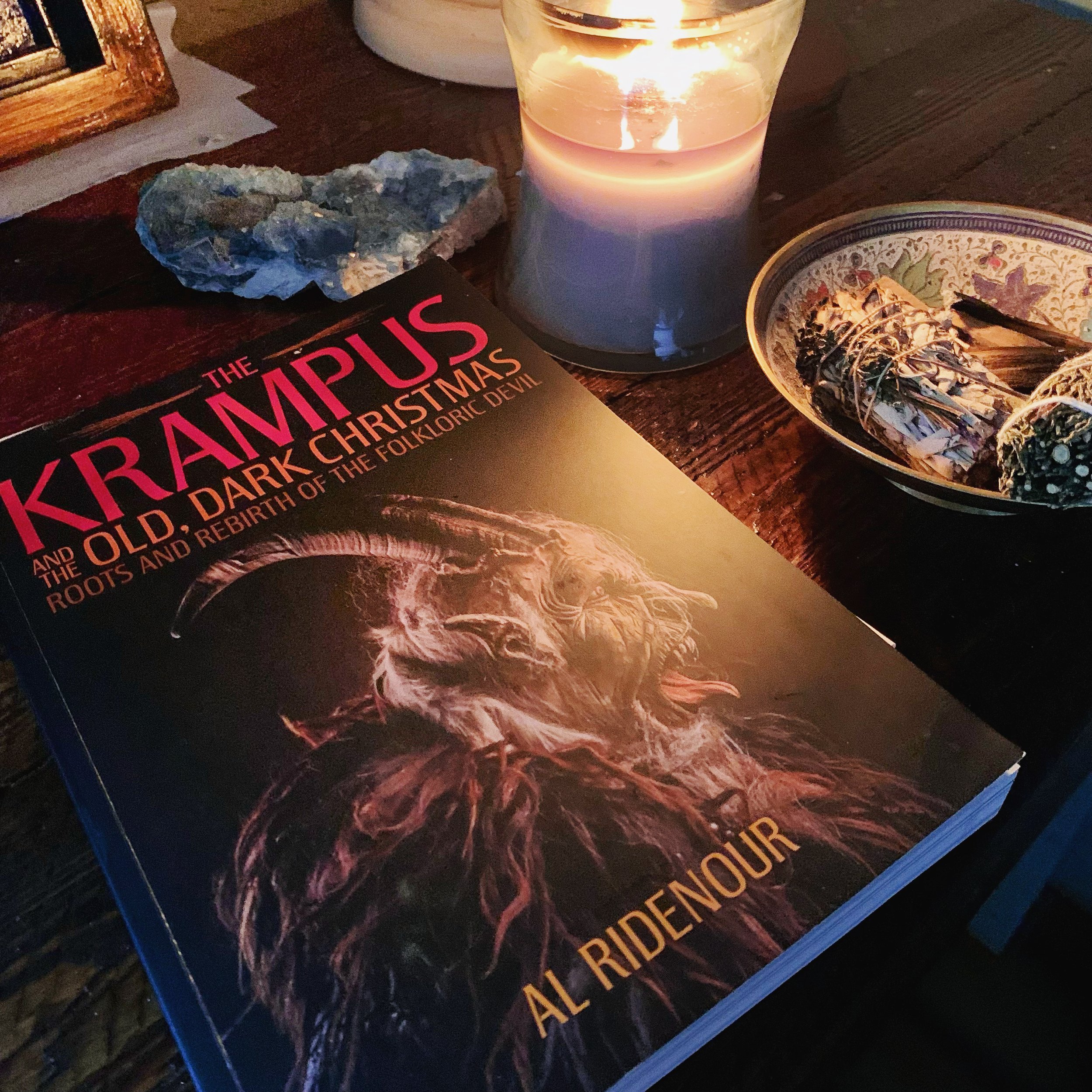

Passage from “The Krampus and the Old Dark Christmas,” by Al Ridenour

Intro: Happy Yule!

Welcome! Started recording on the night of the Winter Solstice–the longest night of the year

Time Stamp: Where we’ve been this past month

Shout out/Thank You to everyone who has supported us as a new business!

Quick review of our first Holiday Season–markets, making, packaging, procrastinating personal gifts

Where are we going this episode?

Fascination with where traditions come from

Exploring the history of Yule: what is it, and where did it come from?

Love the stories, and mythic wonder of this magical season

Share a bit about how this is my favorite time of year to travel

Onward to explore Yuletide origins…

What is Yule?

Yule History

Yule Customs & Festivities

Characters of the Old, Dark Christmas

ITALY (Strega Befana)

AUSTRIA (Saint Nikolaus, Krampus, Perchten)

WALES (Mari Lywd)

Holiday Season Wrap Up

Thanks for listening!

Resources/Show Notes

“Christmas requires the darkness. Every child understands that it’s only at midnight the Christmas mystery unfolds. The holiday we’ve spun from sugarplums and annual TV specials can’t exist without those dark edges where imagination blooms. Not by chance it aligns with the long, black night of the solstice and Nature’s last breath. Skeletal trees or howling winds aren’t required. Even those who’ve grown up with the hum of Christmas air-conditioning have felt the uncanny as they await that curious night traveler traversing skies in archaic costume and prophet’s beard.

Come late November, the child’s world of consensual reality begins to dissolve—magic elves crouch and spy in suburban homes, still-moist pines are suddenly hauled indoors, and parents whisper and sleepwalk through rituals they can’t explain. Tradition lies heavy as if overseen by long-departed ancestors.”

Travel photography is from our trip to Nuremburg, Germany

This is a passage from the initial pages of Al Ridenour’s incredible book, “The Krampus and The Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil.” On this episode of The Enchanted Path, we’ll be exploring the deep, ancient roots of the midwinter season, and the many colorful, iconic characters that shape our experience of the holidays.

INTRO: Happy Yule!

Season’s Greetings, and Welcome!

It’s the holidays, and I am wishing you all the happiest of Yule tidings! I’m actually starting this recording on the night of the Winter Solstice–the longest night of the year, and peak of the midwinter season. This has been an especially significant time of year for humanity for centuries, long before we began recording our history. It’s a time that’s particularly special to Brian (The Grumpy Gnome) and I, as we’re usually off traveling abroad during the earlier part of December. This year and the last, of course, have looked very different with the effects of the pandemic. It’s actually been more difficult for me to feel the spirit of the season this year, with everything going on in the world. But, in turning to research for this episode, it helped me appreciate that the traditions surrounding Yule, the Winter Solstice, Christmas, Hanukkah, and the innumerable, wondrous ways to celebrate all share very old, deep roots across our many cultures worldwide. The holiday season has weathered the storm of every major war, crisis, plague, and catastrophe. And even if things feel different this year, the intrinsic magic of this beloved time will prevail and guide us to better days ahead.

It’s been a bit since I released an episode, and I wanted to take a moment before we get into this one to share where I’ve been. It feels amazing to hop back onto the Enchanted Path with you all! The Grumpy Gnome (Brian) and I are new business owners, and this has been our very first holiday season in that new role. We’ve been completely immersed in this aspect of what we do over the last month, between our online stores and local market dates. We’ve experienced THE BEST first season we could have hoped for! We met incredible people, learned a ton, and enjoyed the process of figuring it all out together. The post office is slowly becoming my second home–I’m there just about every day shipping out orders. We work out of our home, and I’ve been reorganizing parts of the house and studio as we go to make more space for things like inventory, shipping supplies, extra scissors and packing tape… And the markets—they were so awesome! I really want to thank everyone who came out to see us and support our shop. It was a joy to do, and I can’t wait to pick back up when the season starts again next year! The only drawback is I definitely procrastinated all of my personal gifts for friends and family, so they’ll likely be receiving presents after Christmas. But, through researching the history of Yule, I learned that there’s technically twelve days to celebrate…so I won’t be all that late.

I’ve always been fascinated with where traditions come from. This interest led me to the topic of today’s journey, where we’ll be exploring the origins of Yule and some colorful, mythic characters of the season. I love to discover the stories behind the legends–they exalt the sense of mythic wonder that illuminates perception. I find it especially interesting to follow the connective threads across history, and to look at how beliefs evolve into our present day. It’s my absolute favorite time of year to travel, especially internationally. Approaching different cultures with an open mind and heart, sharing in celebrations across different places–it gives powerful insight into how we are all connected, in the most joyful of ways.

For those who are interested in astrology, I find the parallels between Sagittarius Season and these desires to be really interesting. Sagittarius is a sign of the zodiac that rules travel, expansion, and the spirit of all things adventure. It’s all about learning and evolving through a collective experience. Sagittarius is also ruled by the planet Jupiter, which is the great giver & expander of the solar system. When I imagine a face to this energy, it’s definitely personified in the jolliest, loudest incarnation of the Ghost of Christmas Present, from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

But anyway, back to the main topic! Travel and the history of Yule. What is Yule, exactly? The idea conjures images of crackling fires, spiced drinks, rustic decor, evergreen boughs, live music, and the enveloping warmth of old-world charm. But where does it all come from?

What is Yule?

Yule is, at its essence, a time when we bring Light into the Darkness.

The earliest-known mention of the term “Yuletide” was recorded in the 15th century. “Yule” is derived from the Old Norse “jol” and the Old English “geohol.” It references a large celebration or feast. “Tide” relates to a period of time. In the case of “Yuletide,” it was a series of days during the midwinter season. The Yuletide was a multi-day event that was part ritual, part celebration. It marked a season of hunting after the end of the harvest, occurring between the final week of November and the day of the Epiphany in early January. Yule was intentionally centered around the darkest time of year, and began on the night of the Winter Solstice. This time was chosen because Yule was symbolic of bringing light to the longest night of the year, heralded as a time of great mirth and reverie that defied the bitter winter cold. The festivities typically lasted twelve days, running from around December 21st through the first of January. This was a celebration of nature, of a seasonal change—a time of joy and gathering, steeped in a ritual that would help ensure the winter’s end and a bountiful harvest to come.

The earliest records of Yule traditions span the northern region of Europe, in the snow-capped climate of Scandinavia. Even though the most familiar symbols of Yule originate in a European framework, Winter Solstice celebrations have been a part of mankind since the time of our earliest ancestors. It’s a universally significant event that was recognized by diverse cultures across the globe. Religious observances were established in conjunction with specific festivities, including great feasts, communal fires, drinking, storytelling, and the ceremonial hunting of animals. The sacrificial blood of animals is a common theme across cultures, probably because they would not have been able to feed the entirety of their livestock through the winter and depended on meat for sustenance. Symbols of renewal decorated interior spaces, including evergreen boughs, lit candles, and hearth fires, evoking hope for the return of spring.

Yule was also a time of oath-making. Relationships in business, marriages, and all types of commitments were presided over by the priests, chieftains, and spiritual leaders who held the authority to consecrate them. Today, we often use the transition of the new year to make commitments to ourselves in the form of resolutions.

Gradually, the dates of Yule shifted to coincide with the time that Christmas was celebrated, as Christianity rose to prominence across Europe. During the 4th century, the celebration of Christmas was designated on December 25th. Why this date? Well, this was previously a Roman holiday known as Saturnalia– “The birthday of the invisible sun.” Saturnalia was a time to honor the Roman god Saturn, who ruled agriculture and governed prosperity. It was a time when the social order of ancient Rome was inverted, and wild reverie took over society. On this day, schools and work would stop–even for those who were enslaved. People decorated with wreaths and greenery. They held feasts, enjoyed drinking, exchanged gifts… The upper classes in Rome celebrated Mithra, the god of the unconquerable son. It was among the most important days of the year.

At this time in history, December 25th was recognized as the date of the winter solstice, in this part of the world. The old religious, sacrificial traditions were eventually left behind, but the communal celebrations persevered. Christian leaders decided to celebrate Jesus as a human being, in the form of a child who came into the world by immaculate birth. This decision led to the choice of December 25th as the feast day of the Nativity, even though some scriptures indicate that Jesus may have actually been born in the springtime.

In assigning the Nativity to this time of year, the Church was able to merge ancient pagan traditions with Christian religious observances. However, they also relinquished agency as to how the holiday was celebrated. The customs surrounding Yuletide were deeply ingrained across cultures and could not be completely uprooted or transformed. The Church decided to adopt the Pagan traditions, rather than attempt to eradicate them. “Christ’s Mass” became “Christmas.” Eventually, the raucous, debaucherous street party that surged at Christmastime cooled to the gentler kinds of familial & community gatherings we observe today. The 17th century was a particularly strong turning point, when puritanical religious leaders sought to exert their authority and overturn the old ways.

Essentially, Yule and Christmas are different celebrations with culturally blended practices. These customs all connect to the deep symbolism of this wondrous time of year surrounding the solstice, and the bringing of light into the world. At its heart, this season is a time of renewal, release, and the joy of moving into brighter days.

Many of the colorful traditions of Yule were adapted across history, and continue in some form to this day.

The lighting of the Yule Log is perhaps the oldest tradition that has survived. Originally, an entire tree was carefully chosen and felled for the occasion. This exceptionally large log was hauled indoors with great ceremony, where one end was placed inside a large hearth. The log was lit on the first day of Yule, and gradually burned over the course of the twelve days. It was believed that each spark from the Yule log represented a new birth in the coming spring. People took turns attending the fire, as letting it burn out was believed to bring bad luck. When the final day had ended, the remaining unburnt portion of the Yule Log was stored for the following year, where it would start the fire of the next Yule celebration.

Today, the tradition of the Yule log surfaces in our affinity for gatherings around a hearth fire. Hours-long videos of a log burning in a crackling fire can be played on monitors and screens. Special desserts rolled into the shape of a log, often made from layers of sponge cake and buttercream, are also a nod to this ancient tradition.

Another symbol of the season is the Yule Goat. It is said that the Norse God Thor had a chariot that was pulled across the sky by two great goats. During Yule, the goats would either bring gifts to well-behaved children, or demand offerings to Thor from the not-so-good ones… Over time, the Yule Goats transformed into the flying reindeer who pull Santa’s airborne sleigh, rather than Thor’s celestial chariot.

In Sweden, small goats made of straw are one of the most popular Christmas decorations. There is a strange and fascinating tradition surrounding a very large Yule Goat in the town of Gavle, Sweden, that has gained international fame. Since 1966, every year in the town square, a giant, 42’ tall, 3-ton straw goat is constructed for the Christmas holiday.

However, this enormous statue made of super-flammable straw has drawn some unfortunate attention–there are constant attempts to burn down or demolish it. Within a 50-year period, the Gavle Yule Goat has been destroyed 35 times! Despite the best security attempts of the town to protect the goat, efforts to undermine them have been quite creative. One year, assailants dressed as Santa and the Gingerbread Man fired flaming arrows at the goat, successfully destroying it. Another year, hackers disabled the security system and set the goat ablaze. In 1976, someone drove a car into the back legs and collapsed the entire statue. One year, there was an effort to abduct the goat by helicopter–though this attempt was not successful. Despite the serial attacks on their beloved Yule Goat, the town of Gavle is committed to keep this tradition going. And their Goat has been featured in the Guinness Book of World Records, for its massive size. Pretty impressive, all around!

What would the holidays be without classic drinks? Holiday Nog comes from the word, “grog,” referring to basically any drink made with rum in it. Another favorite is wassail, a delightful punch made from alcoholic fruit juice and seasonal spices. Wassailing roughly translates to “To Good Health”--a toast to everyone’s well-being in the days to come. And a “toast” was given because toasted bread was traditionally served with this drink. Going “wassailing” was originally an orchard blessing ritual, where revellers would roam the streets from door to door singing and asking for wassail or figgy pudding. The boisterous procession would conclude in an orchard, where they would make enough noise to “wake up the trees” from hibernation during the longest nights of the year. This joyous practice evolved into singing in the streets and caroling from door to door. Instead of wassail, carollers sing for rewards like hot chocolate, eggnog, and cookies.

Food held special significance during Yuletide. Annual wild hunts and the sacrificial slaughtering of livestock were all performed in conjunction with the solstice, in service to the gods. This was the time of year when meat was most abundant, as it was very difficult to sustain all of the livestock through the winter. The Norse god Odin’s name was associated with this midwinter holiday, as he would determine who prospered or perished in the coming year. Pigs and wild boar were traditionally sacrificed to the Norse Goddess Freja, who held the power to bless marriages and children. People gathered together indoors for the annual feasts of Yule, protected from the cold and roaming spirits outside. Today, we see echoes of this custom surface in the tradition of preparing a Christmas ham and gathering for a large meal.

The presence of evergreen trees is deeply significant to Yuletide. Boughs were harvested and brought indoors to affirm the continuation of life. Mistletoe was especially important, and revered as a magical plant by the ancient Druids and Norse people. Mistletoe remained green long after being cut from the host tree, and drew nutrients without any roots in the earth. It was always found high up in sacred trees, like oak and apple. The mistletoe was cut ceremoniously, and pieces were handed off to every household to ward off evil for the following year.

The tradition of Christmas trees emerged from this same kind of intuitive relationship, between the evergreen and the continuation of life. The custom of bringing a tree into the home and lighting it for Christmas gained great popularity in the 1840s in Victorian England, which was soon followed by Americans. It soon became a beloved tradition and a natural part of the Christmas holiday.

The concept of light as a guiding force from the darkness is perhaps the most important symbol of Yule. Christmas lights, candles, and fires are set ablaze during the midwinter season to this day, across many cultures. The star above Bethlehem is a beacon for the Christ Child entering the world. Appalachia has a curious superstition in relation to candles–it is customary to never leave a candle wick unburnt. You always burn the wick, even just by a little, to ensure good luck.

Characters of the Old, Dark Christmas

ITALY

Our first stop on the enchanted path lights the way to Italy! Buon Natale!!

Italy is a rich, beautiful, diverse nation with a variety of gift givers in the Yule season, depending on where you’re from. In metropolitan areas of Italy, Babbo Natale (or Santa Claus) is a popular visitor. On the night of December 5th, children leave their shoes by the fireplace or outside the door, and wake up the next morning to find gifts and sweets from San Nicola.

Santa Lucia, or Saint Lucy, has a special holiday on December 13th. This tradition is native to north eastern Italy. Kids write a letter before she arrives, asking for presents. On the evening before December 13th, a plate with cookies and food are prepared, as well as hay for the donkey. Santa Lucia’s visit comes with a stark warning–kids must stay in bed, because if they wake to sneak out and spy on her during the night, she’ll throw ashes in their eyes.

She rides a donkey from house to house, delivering presents that excited kids wake up to find in the morning. The Christ Child, or baby Jesus, is another gift-giving figure who is said to deliver presents to children on the eve of December 24th, or on Christmas morning.

The main character we’ll be focusing on during our time in Italy is none other than La Befana, the Christmas Witch. She’s also referred to as Strega Befana–no worries though, she’s a gift giver–a good witch! La Befana is most popularly personified as a very gnarled, old, benevolent lady–almost like a fairy godmother figure. She has a weathered but kindly face, with a long, curved nose and a headscarf knotted securely below her protruding chin. On the Eve of Epiphany, the night before January 6th, La Befana travels by broomstick to deliver gifts to the children of Italy. She is often portrayed with a sooty appearance, as she arrives by climbing down the chimney of each home. Good boys and girls have toys and sweets to look forward to from La Befana’s visit. However, kids who were not so good will receive coal, or “carbone,” in their stocking. The customs surrounding La Befana’s visit are similar to the way Santa Claus is celebrated; however, instead of leaving out milk and cookies, La Befana has a glass of red wine and Italian cooking to look forward to. Legend has it that if she’s happy, she’ll sweep the floor before she leaves.

What exactly is La Befana’s story, and how did she come to be so significant around the Yuletide season? Her origins are connected to the time of the birth of Christ. The story begins over 2,000 years ago, when La Befana lived in a lonely cottage. One morning, she was sweeping outside on her front porch when a caravan of camels approached with a group of men. They spoke in a language strange to her ear, and appeared to be very excited while pointing to the sky. La Befana overheard them mention the name “Bethlehem,” and they were following a big star in the sky. The light was leading them to baby Jesus, the young king who had just been born. These strangers invited La Befana to accompany them, but she declined–even though in her heart, she wanted to. A shepherd passed her cottage a few days later, sharing the wonderful news of the new king and birth of the son of God. The sky opened with brilliant light, and the sound of angels singing. La Befana decided to follow the direction of her heart. She wanted to go, more than anything. She searched her home for a gift–all she had was a small, humble doll made from wool, but decided that would be better than nothing. When she emerged from her cottage to follow the star, her heart sank–she could no longer see it. The shining light in the sky had faded from sight.

Ever since that day, La Befana searches on the eve of the Epiphany for the Christ Child. She travels to every house and climbs down every chimney with gifts to give to the children of the home. Excited kids wake on the morning of January 6th to find what La Befana has left for them overnight.

The festivities surrounding La Befana hail from the medieval village of Urbania. It is here that the Festa della Befana is held annually. Parades, music, dancing, open markets, and great food are all a part of the celebration. Booths serving fire-roasted chestnuts, or marroni, Spiced Wine, or vin brule, and Crostolo–a flatbread made with pork lard–are all staples of this event. Costumes are worn to impersonate La Befana, complete with long warty noses, head scarfs, and wooden brooms. The winter holiday season is a time of great celebration in Italy. Storytelling, great food, gift exchanges, singing, and dancing are all a part of this incredibly colorful, festive time of year.

AUSTRIA

It’s time for our journey to take a darker turn, to the majestic peaks of the snowy Alps. The shimmering of bells echo across steep valleys and evergreen forests, shaking the night to life. Thousands of hoofbeats sound in the distance, an approaching thunderstorm of breath and fire and roaring, running beings. The light of the sun has given way to a cold and haunting moon. Flames erupt in the open street. The night of a thousand devils has begun.

This is a brief description of my experience on an electric December night in the misty town of Bad Goisern, Austria–and what the atmosphere feels like just before a mammoth outdoor event known as Krampuslauf begins. It’s easily one of the most amazing things Brian and I have ever experienced on our holiday travels!

Krampuslauf, or the Krampus run, is an annual event that takes place around St. Nikolaus Day on December 6th. It’s a tradition mostly concentrated in the Bavarian Alpine region of the world, and strongest in Western Austria. Though, the tradition does span Southern Germany, the Tyrol region of Italy, and Northeastern Switzerland. There are multiple events that stagger across early December, from small towns and major cities. Each locality has their own “pass,” and a distinctive identity in their presentation and mask styles.

Krampuslauf events are hosted at a variety of scales, from local parades through sleepy mountain towns, to huge celebrations in the open markets of city squares. Usually, streets are barricaded in advance to establish the route the Krampus will be taking. People line up along the waist-high metal railing, and pack in tightly for the best view possible. The event traditionally takes place at night–though some major events, like the Krampuslauf in Munich, are held during daylight hours. At the head of the Krampuslauf, a St. Nikolaus figure draped in long robes, a tall hat, and a walking staff leads the procession. He’s a benevolent icon of the Christmas season, who passes out candy and sweets to the children lined along the street. Sometimes, he’s accompanied by women dressed as angels, who help pass out the candy.

Following St. Nikolaus’ lead is a wild, energized stream of towering, charging Krampus figures. Each one is dressed in shaggy fur and tattered cloth, with long, protruding horns and astonishingly detailed, hand-carved and painted wooden masks. They wear enormous bells attached to the back of a wide belt, and often pause to shake them in unison. The sound is unbelievable, and you can hear it coming from literally miles away. Their breath is visible through the mask against the frosty air, and the authenticity of their costumes creates this visceral experience of each one seeming alarmingly real. The Krampus will lean in closely, right up to your face. Generally, they don’t speak–they mostly roar. Occasionally, they would whisper something to me in German–though even if I understood the language better, I wouldn’t have been able to hear through the boisterous excitement of the crowd. The smell of gunpowder, animal fur, and leather follows them. They move quickly, sloped forward with menacing intent and long, pounding strides. With surprising athleticism, they dart swiftly from each side of the street, vigorously shaking the metal barricades, stealing hats, and whipping people’s shins with birch switches. One of them bent Brian over the railing and spanked him, I don’t think I’ve ever seen him quite so happy. We watched the Krampus pick up kids and carry them around the middle of the street before returning them to their parents. And the kids, delighted and remarkably calm, all seemed to enjoy the experience. When we were there, all the Krampus seemed extraordinarily tall to me–probably a combination of my 5’-2” height and the fact that they are made even taller by their impressively long horns. In a place where people tend to be taller in general, I blended in with the kids like a wayward elf.

So, maybe I should pause–who and what is Krampus, and what the hell am I describing?

Gruss vom Krampus

Over 1,000 Krampus combine forces with the local Fire Department to ignite the misty streets of Bad Goisern, Austria, in celebration. From Krampuslauf, December 2017.

Let’s dive into a little history…

“Krampus” does not really refer to an individual character, but to a class of entity. The name is thought to derive from the Middle German “Kralle,” or “claw,” or from the Bavarian term “Krampn,” which describes something lifeless and shrivelled. The Krampus has a connection to the spirits of the dead, which may help explain this association. When we were in Austria, I most often heard the Krampus referred to as “the devils.” As Prostestant ideals overtook Catholicism in this part of the world, St. Nicolaus transformed into a gift-giving figure accompanied by a variety of “dark companions.” The Krampus, Servant Ruprecht, Frau Perchta, and The Perchten are but a few of these characters who roam the world alongside St. Nicolaus during this dark and mystical season. These characters of folkloric and eccliastical roots shape what is referred to in German as the Kinderschrekfigur, or “child terror figure:” a pairing of a reward-giving entity with a threatening one that strongly encourages children to behave. There are a number of nightmarish predecessors to the Krampus who once fulfilled this horrifying role. Among them are a night raven, a night goat, child-gobbling ogres, and towering men with sacks or baskets filled with naughty, crying kids…

While this all may sound absolutely terrifying, I assure you that the actual experience of going to Krampuslauf is wonderfully exciting, thrilling, fascinating, and fun. In this incredibly special winter time where all things are possible, magical beings emerge from the shadows of the imagination–however beautiful or formidable–and come to life.

In some regions, there is a tradition where St. Nikolaus makes house calls. These visits are usually directed towards children around ten or twelve years of age. Travelling from door to door with his companions, St. Nikolaus enters the home with his angels and his basket carrier, and recites a verse to the family. While this is going on, the Krampus are usually lurking outside or hiding in some unseen part of the house. Most of the verses are written by the people reciting them.

Here’s an example of one poem, loosely translated into English, by Gasteiner Patrick Deisl:

“God’s greetings, all within this house!

I’m friend to all, St. Nicholas.

Have no fear, just look at me.

No wild stranger here you see.

My coming marks the year’s new end.

This Forest Man my basket tends.

Deeds good and bad we must review.

With ringing bells comes Krampus too,

What brings him joy brings terror to you.”

After this greeting, St. Nikolaus may open a golden book and read about the children’s behavior (the details have likely just been whispered to him by their parents), or he’ll ask them directly about how they’ve been doing this year. Before they can receive their gifts from St. Nikolaus, the children must recite a poem or sing a song to him that they’ve been rehearsing in the weeks leading up to this event. The children are then rewarded with a small stocking from the basket containing traditional treats like nuts, mandarin oranges, apples, and small chocolates shaped like St. Nikolaus or Krampus. Sometimes, holiday gingerbread cookies known as Lebkuchen may be included. The local troupes organize the event and prepare all the treats for the children in their town. Often, there’s a small twig attached to the gift as a nod to Krampus’ switch, and a card from the troupe, or Pass. The highlight of the visit, of course, is the reveal of the Krampus. They usually come out after the gifts have been handed over, making as much noise as possible and chasing the family around their dining room table. Bells sound with deafening thunder and the whole house shakes, and they momentarily defy St. Nikolaus and brandish their switches wildly. Eventually, the Krampus depart under the Saint’s command–but their appearance at the end of the visit is a clear warning to be good, until next time….

Throughout Austria in early December, you may encounter signs advertising an event called “Perchtenlauf”--but who exactly are the Perchten, and how do they differ from Krampus?

Essentially, Perchten are old Alpine spirits of the wilderness, divided into two classes–the Schonperchten, which means “good” or “beautiful” – and the Shiachpercht, meaning “bad” or “ugly.” Our modern image of Krampus was certainly modelled after the Shiachpercht. Visually, Perchten are incredibly similar to Krampus, dressed in the same mask, horns, fur, and bell-adorned belt. Where Krampus traditionally has two horns, a Percht may sport as many as four or more. He carries a horse-tail whip to strike passersby, just as Krampus does with his switch of bundled branches. The most fundamental difference between the Perchten and Krampus is that a Percht is a pagan figure, and the blows dealt are not to punish bad un-Christian behavior, but rather, to drive away the darkness of the winter. Perchten make a ruckus in the streets and strike at things to scare off malevolent spirits, clearing the path for good luck in the coming season. Another key difference is the time of year. Where Krampus is affiliated with St. Nicolaus Day on December 6th, the Perchten are more closely connected to the Epiphany holiday on January 6th. The foreboding goddess Perchta is the source from which Perchten have evolved, and she is deeply associated with the end of the year and the domestic order.

Frau Perchta is a fierce supernatural authority on domestic responsibilities, demanding that all the household tasks be completed before the years’ end–or else, the consequences will be severe. Flax must be spun, floors swept, and homes tidied in time for the new year, or she would execute a series of gruesome punishments on the residents therein. It was warned that she would burn the hands of lazy spinners, or slit the belly open of those who ignored their chores and stuff their bodies with straw and refuse. She is often portrayed as a witch-like figure, with a sooty face and bedraggled hair, carrying a coarse wooden broom. Despite this image, her name is closely derived from the name of Epiphany, meaning a “shining light.” Ultimately, Perchta is a being of duality–embodying the dark and the light as one entity. She holds the capacity to generously reward and cruelly punish, in accordance with the deed.

WALES

As we close in on the New Year, we’ll conclude our Yuletide journey with a visit to Wales, to learn the story of the Mari Lywd.

This tradition is a pre-Christian folk custom unique to Southern Wales that would occur around the end of the Yuletide season. There are many different variations of this tradition, and it can range from a single night event to a multi-week celebration. The main character of this tradition is the Mari Lywd herself–a horse figure associated with death and fertility. “Mari Lywd” roughly translates to “grey mare.” She is a feminine, haunting figure–a bare horse skull with an articulated jaw, mounted atop a pole. The horse skull was typically fashioned with false ears and eyes, complete with reins, bells, dangling braids, and colorful ribbons.

A white sheet or shawl was draped below the horse head and wrapped around the person carrying the pole. Often, the ribbons and fabric for the Mari Lywd’s ethereal body were donated by women of the community. Additional decorative elements, like painted spirals and evergreen branches, can also be incorporated. Every personification of the Mari Lywd is unique to the community creating it.

Even though the Mari Lwyd can seem spooky at first glance, she was a positive figure believed to bring good fortune to the households she visited. Her origins are murky, but may have emerged from the reverence of horses in sacred beliefs of the ancient Celts. Throughout Celtic lore, there are many instances of people transforming or communing with animals in the dark months of winter. Horses held a connection to fertility, evoking abundance of the land and the animal kingdom. Many Celtic coins from the Iron Age are stamped with images of horses, indicating that the horse was a symbol of prosperity. In later Welsh folk tradition, it was custom for newlyweds to travel home by horseback after their marriage ceremony. However, it was imperative that they trust the horse and allow it to freely lead the way. If they tried to take the reins and steer the horse themselves, it was warned that they would inevitably be childless.

It’s impossible to know exactly how old the Mari Lywd is, though the earliest written reference can be traced to a performance in the early 1800s. This ghostly horse figure likely originated from the concepts of fertility and death–she may have roots in a fertility ritual that began before recorded memory in the middle of winter, to try and ensure the return of the spring. In an interview I watched, one man who grew up in the 1950s recounted his father describing the Mary Lwyd to him as a child. He remembered the legend as a ghostly white horse, who would emerge from the mist and take children away in the night if they didn’t behave. Although his personal account presents a somewhat threatening connotation, most theorize that the presence of the Mari Lwyd was intended to drive out any dark spirits from the houses she entered. The expectation of the household when the Mari Lywd visited was to feed her and the accompanying singers, providing nourishment.

Sometime around the Christmas and Epiphany holidays, the Mari Lywd would be carried with a party of people from door to door at dusk. This company was usually drunk, and would recite Welsh poems and verses in boisterous song.

Those inside the house would rush to lock their doors and windows when they heard the group approaching, and replied in verse to resist the entrance of the party with the Mari Lwyd. Through the closed front door, the two parties would battle in an exchange of witty banter and playful insults both sung and shouted. The group outside the door would be filled with drunken laughter, their lanterns illuminating their faces with warm, flickering light. Eventually, the wandering party would win and be allowed inside for food and drink. The Mari Lwyd would chase the women and children around the house, clacking its long jaw, and playful havoc would ensue. The entire occasion was a wild, raucous dance of an affair. After food and drink was finished, the house would be swept and cleaned, and the fire relit before the Mari Lywd departed. This departing task can be interpreted as a way to reset the home in preparation for the coming year, thus clearing the path for a new “tide” of fruitfulness and abundance.

Every year, the Mari Lywd horse skull was stripped of its decorations and buried in the earth. This action, of covering the skull in soil or lime, ensured that the bone wouldn’t yellow with age and could maintain its whiteness. It was typically looked after by one family in the community parish. In some instances, it was kept inside of a local pub during the off-season. Like an embodiment of the cycle of life and death, each year, the Mari Lywd skull was revived from the earth and later returned.

Mari Lywd parties carried a strong reputation for drunkenness and vandalism, and were gradually replaced by the gentler Christmastime tradition of carolling from door to door. The classic battle of versus and insults in Welsh gave way to songs performed in English, and by the end of the 1960s, the custom of the Mari Lywd had all but died out.

Today, the Mari Lywd is being revived across certain areas of Wales–but with slightly less emphasis on the drunken vandalism. This tradition is being embraced as a way to acknowledge and celebrate a modern Welsh identity, and bolster uniquely Welsh traditions against the pressure of overpowering influences from other cultures abroad. Some of those who participate wear old fashioned clothing, or traditional Welsh dress. It sounds like a pretty fantastic time, and I certainly hope that one day, I’ll be able to travel to Wales and experience this tradition firsthand.

Holiday Season Wrap Up

And with that, this season’s Yuletide adventure has come to a close. I hope that you enjoyed this walk down the enchanted path, and if nothing else, learned something interesting. It’s a magical time, the holidays. And midwinter. I think what compels me to it is the phenomenon of it being a shared experience across the world, through many different expressions, incarnations, and traditions. Every year that we’ve been fortunate to travel during this time, we learn so much. And have the absolute best experiences! Even if the weather is rough, and it’s bitterly cold. Even if we get completely lost and miss our train. There’s always something to discover and appreciate along the illuminated pathways of the Yuletide season.

I’ll include links to some of our highlights from holiday travel in the show notes, and have plenty more stories to share. But for now, it’s time to go celebrate. I hope you all have a beautiful holiday, and a wonderful new year!!

Thanks for Listening!

Thank you so much for joining me on this journey into the world of Yule lore, the mythic side of midwinter, and ancient holiday traditions. I hope you enjoyed it! May your days be merry and bright, this holiday season and far beyond.

This episode was written and produced by me, Jessie Howe! You can find all resources and episode transcripts for The Enchanted Path Podcast on my website, The Adventures of Jessie and The Grumpy Gnome, at jessieandgrumpygnome.com. Our podcast is streaming on platforms including Spotify, Anchor, and Apple Podcast. If you enjoyed this episode, please consider supporting the show by joining our Patreon--The Enchanted Path Podcast. Memberships start at just $1, and give you exclusive access to early releases, bonus episodes, artwork, music, custom merch, and monthly gift boxes!

Thank you for listening, and until next time--happy adventures!

SHOW NOTES:

Our Website:

https://jessieandgrumpygnome/the-enchanted-path-home

Our Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/jessie_and_grumpygnome

BOOKS:

The Krampus and The Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil, by Al Ridenour. 2016.

RESOURCES:

https://stores.renstore.com/history-and-traditions/yule-history-and-origins

https://nerdist.com/article/yule-curious-past-and-present-day-importance/

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/Welsh-Christmas-Traditions/

https://rhinwedd.cymru/blogs/news/the-story-of-mari-lwyd

https://www.cbc.ca/kidscbc2/the-feed/the-strange-legend-of-the-swedish-yule-goat

https://www.cbc.ca/amp/1.6290300

https://www.aroadretraveled.com/la-befana-festival-in-urbania-italy/

Do you have any adventurous, memorable stories from your own holiday travels? Or Yuletide rituals and traditions that you love to celebrate? If you would like to share, please tell us about it in the comments below!