“A Call of the Sidhe”

A Journey into the Mystic with Irish Literary Icon, AE

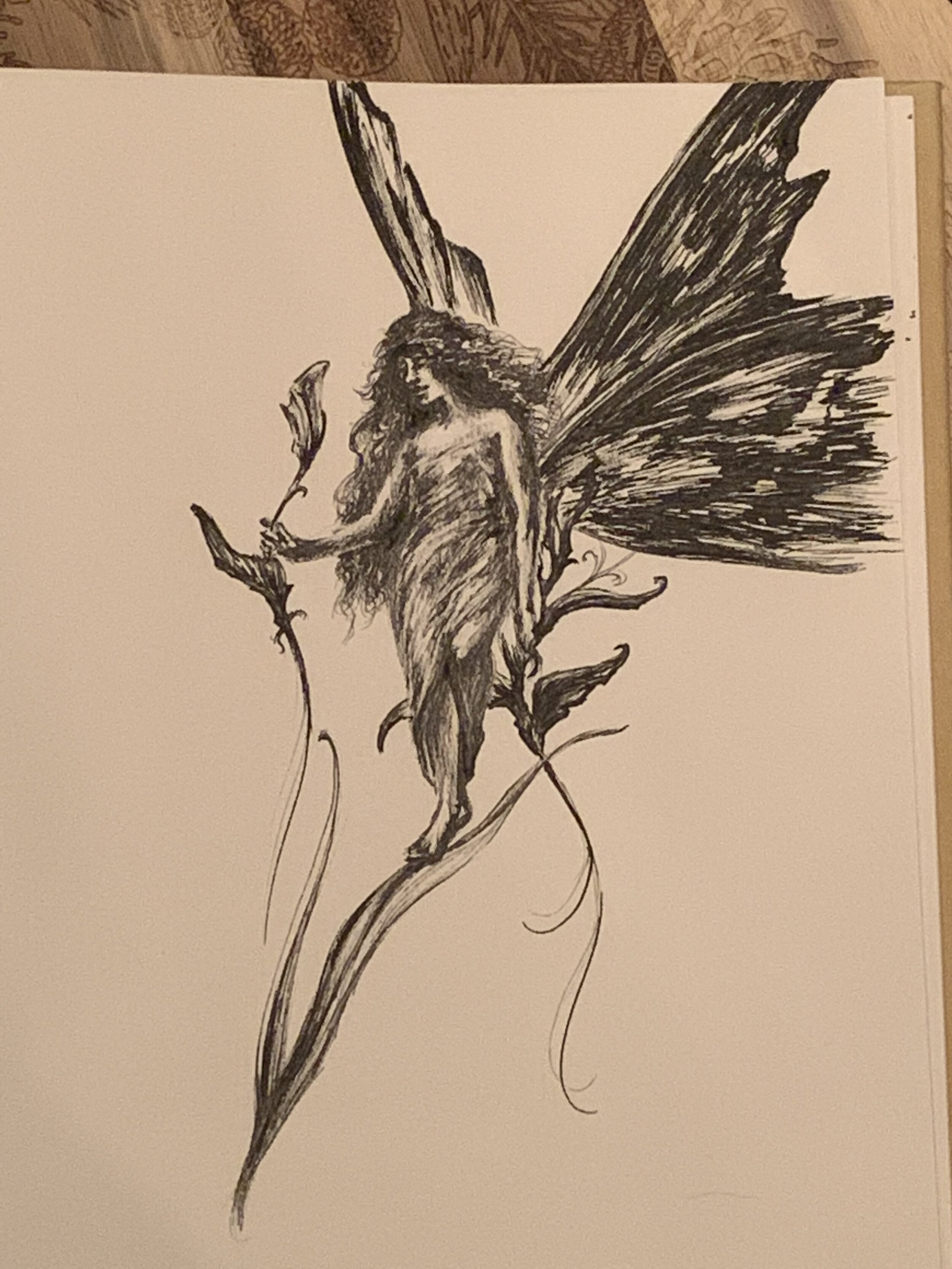

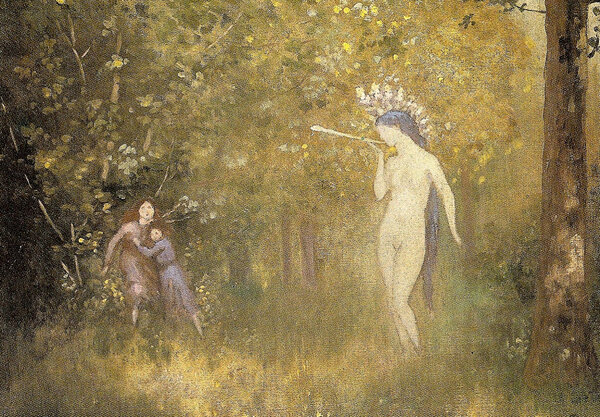

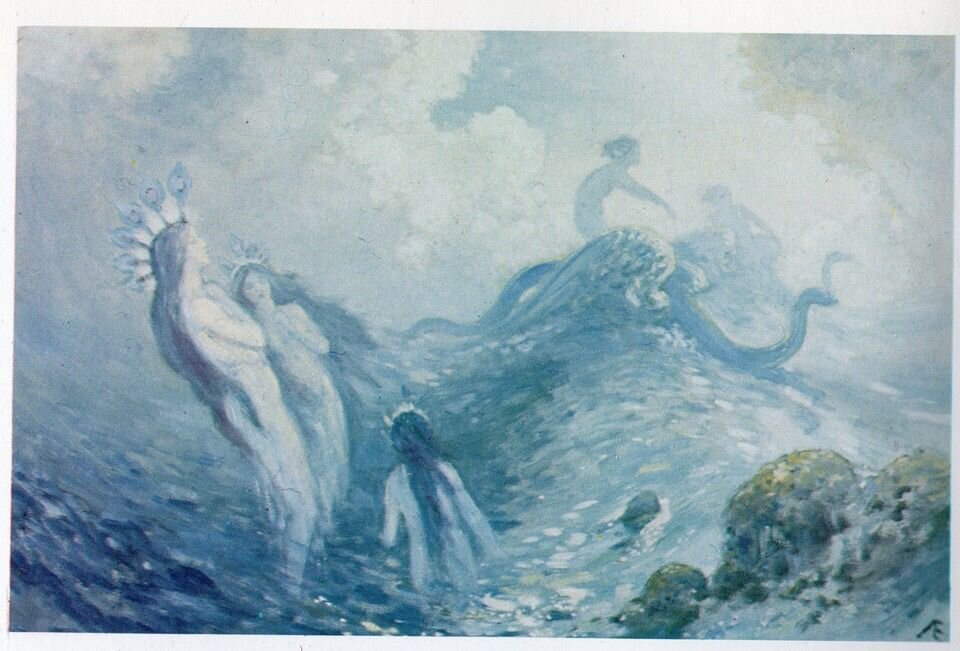

Painting by “AE” (George William Russell)

Today’s Read:

A Call of the Sidhe: A Poem by A.E. (George William Russell)

1913, from Collected Poems

Genre: Poetry, Mysticism, Art, Irish Literature

In the following poem, “A Call of the Sidhe,” AE (the chosen pseudonym of Irish literary icon George William Russell) romances a vision of the ethereal presence that animated the enigmatic, emerald landscapes of his beloved homeland.

A Call of the Sidhe

“TARRY thou yet, late lingerer in the twilight’s glory:

Gay are the hills with song: earth’s faery children leave

More dim abodes to roam the primrose-hearted eve,

Opening their glimmering lips to breathe some wondrous story.

Hush, not a whisper! Let your heart alone go dreaming.

Dream unto dream may pass: deep in the heart alone

Murmurs the Mighty One his solemn undertone.

Canst thou not see adown the silver cloudland streaming

Rivers of faery light, dewdrop on dewdrop falling,

Star-fire of silver flames, lighting the dark beneath?

And what enraptured hosts burn on the dusky heath!

Come thou away with them, for Heaven to Earth is calling.

These are Earth’s voice--her answer--spirits thronging.

Come to the Land of Youth: the trees grown heavy there

Drop on the purple wave the starry fruit they bear.

Drink: the immortal waters quench the spirit’s longing.

Art thou not now, bright one, all sorrow past, in elation,

Made young with joy, grown brother-hearted with the vast,

Whither thy spirit wending flits the dim stars past

Unto the Light of Lights in burning adoration.

—From Collected Poems by A.E., 1913

I first encountered this poem when I was in high school. I remember being in the midst of a long and studious afternoon, intensely conducting research for one of my papers in AP English that was somehow connected to my interest in classic Irish literature. During my search, I stumbled upon this poem--and abruptly stopped. I was instantly captivated, my imagination ignited. I felt and saw these words so vividly that the scene unfolding on the page sprang to life. I wanted to escape into that mystical twilight and paint the vision these verses formed inside my mind. Despite my enthusiasm, I set this to the side to finish my work and failed to bookmark it, or write down the title. It would be years until I found it again.

Fast forward to last week, when I was seeking inspiration for the upcoming projects of this month. I found it! This poem! The first line, “Tarry thou yet, late lingerer in the twilight’s glory” caught me just as suddenly as it had when I was sixteen, in the dusty sunlit air of the school library. This time, I wrote down the title and author--and became instantly curious. Who exactly were the Sidhe? And what did “A.E” mean in the poet’s name? I had to know more--and am deeply fascinated by what I have found.

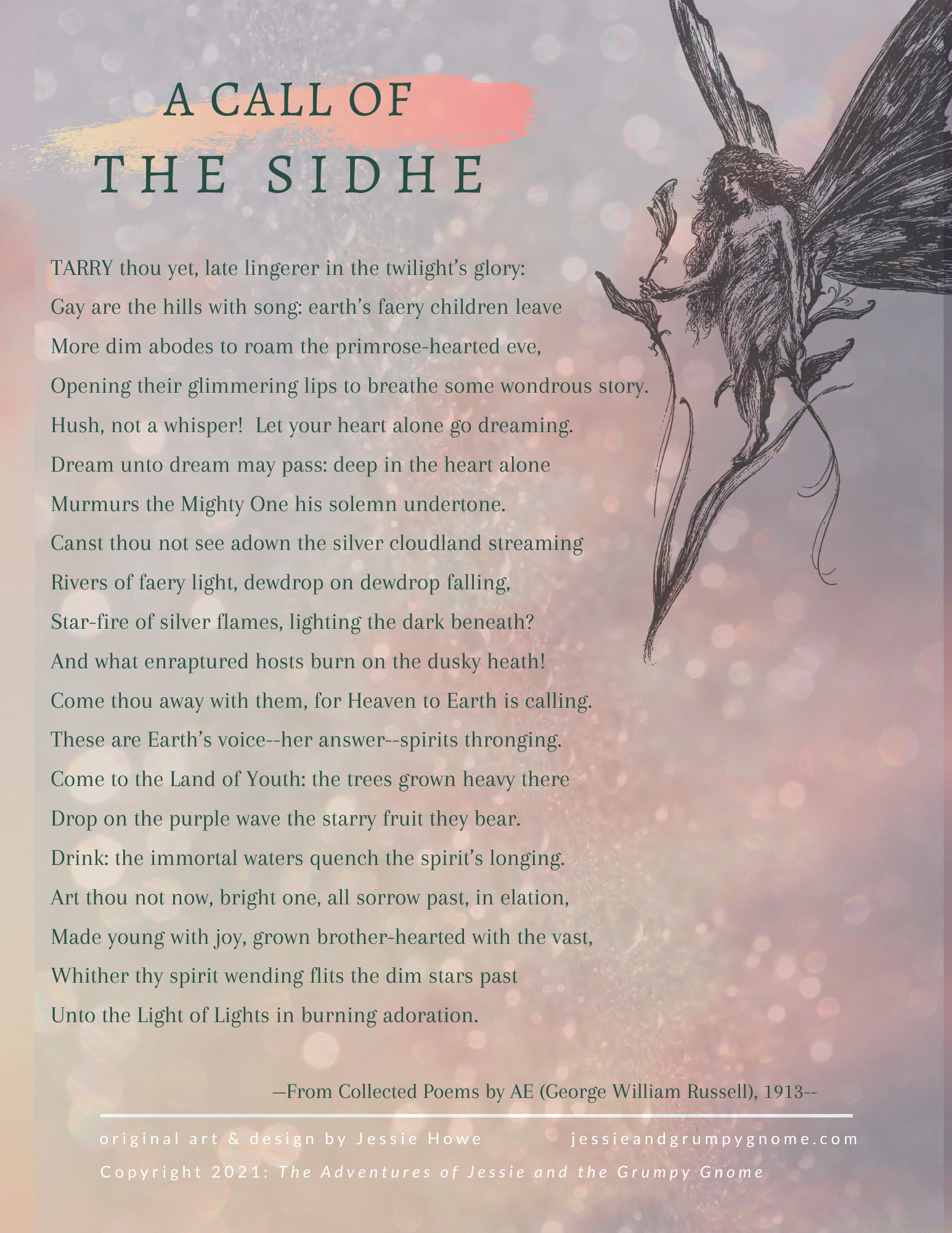

Image to the left is my pen and ink sketch that was inspired by this poem, and the research process.

The late 1800s--the fin de siècle--was a transformative time of innovation and enlightenment. Fascination with the supernatural emerged with the dawn of the industrial revolution, against a backdrop of political turmoil for the Irish. Leading literary figures rose to prominence, creating a renaissance of political, poetic, and mystic origins. The tradition of storytelling is the beating heart of Irish heritage, and so it seems completely natural that some of the greatest writers and artists of the age have emerged from this magnificent nation. Among the legacy of these visionaries was George William Russell, the man who called himself, “AE.”

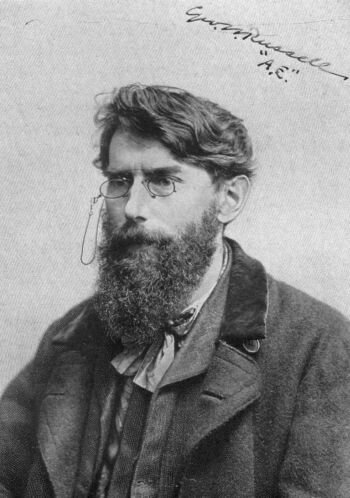

Poet, painter, novelist...economist, editor, journalist...political activist...agricultural expert...theosophist, mystic, literary facilitator and advisor--the roles through which George William Russell expressed himself are as multifaceted as his myriad mind. His breadth of knowledge, talent, and endless interests are legendary. Russell’s reputation as a benevolent mentor and great facilitator to his contemporaries cannot be overstated. From all accounts, he was a person who truly made others’ lives better by being in them. This bearded sage of Dublin, this limitless dreamer, became one of the most inspiring, influential figures of the Irish Literary Revival at the turn of the 20th century.

The first mystery I was intrigued to unravel was his choice of pseudonym, “A.E.” An abbreviation for “Aeon,” “AE” is the entity of an immortal being--the simultaneous existence of the mortal and immortal self. “Aeon” was the term employed by the Gnostics to describe the first beings of creation. Russell was enamored with the mystic realms of consciousness. He held deep reverence for Eastern Religions, was very engaged in Theosophy, and practiced transcendental meditation. “AE” came to him when he was searching for a way to encapsulate the essence of what he was creating through his many facets of expression, and one anecdote describes an experience where the word “AEon” lept out to him from an open book. The concept of “AE” thrilled him, as it evoked a collective of ideas, moods, myths, ancestral memories, and the spirit of the ancient incarnated into one living being. This discovery inspired his choice of adapting “AE” as his true name, and sacred identity.

Image to the right is a Self-Portrait of AE Russell

It seems perfectly befitting that such a person would conjure the words of the poem above. A poet who sought to draw the unseen into visibility, beckoning others to listen to the old traces of Ireland’s enchanting roots through new songs. As A.E. applied human sensation to an omnipotent force, he chose the Sidhe as his subject, who were very much alive in the peripheral of the Irish imagination. “Sidhe” is the Gaelic term for “a mound, or thrust,” and became associated with the Danaan people due to their fabled connection with earthen mounds and barrows. They were powerfully felt, but intangible as the wind. In fact, their presence was believed to arrive through whirlwinds, in “sidhe gaoithe,” which translates to “a thrust of wind.”

These invisible beings had the potential to be heroic or sinister, with a distinct ability to influence the mortal world. The term “fairy” became shorthand for “fair folk,” which surfaced from a reluctance to call the Sidhe by name for fear of bad luck. “Fair folk” was a gentler euphemism that invited more positive interactions. With the capacity to be beneficent or harmful, the Sidhe were respected as exalted supernatural beings living alongside the human world. To this day, specific isolated trees and bushes across the Irish landscape are left alone in reverence and caution for their presence.

A Painting by AE (George William Russell)

Prominent Irish literary figures of the late 19th century, including George William Russell and W. B. Yeats, were born into a rich tapestry of folkloric heritage, and synthesized these traditions with modern mysticism. Steeped in metaphor and metaphysical exploration, the writing, painting, and emerging philosophies of this time explored the existing tension between the spirit world and ours. Cultural roots were deeply entwined with the mysteries of nature. Fairy realms held an association with death, but in this conceptualization, the death was not as literal as a physical one. Rather, it indicated a death of the will and the ego. Interestingly, these ideas were evolving in tandem with the formative years of modern psychology.

There was a kind of imaginative, provocative magnetism to this pivotal period of intellectual development. George William Russell was very much at the center of this movement. He came from humble beginnings, born in the quiet town of Lurgan, County Armagh, on April 10th, 1867. His family moved to London when he was eleven years old, where he eventually attended the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, on Kildare Street. It was here that he met his lifelong friend (and occasional nemesis) William Butler Yeats. Russell was studying to become a painter, and found work at a drapery firm after graduating. It was said that he would longingly stare out the window and dream of freedom during his time there, which I can certainly relate to.

Following the advice of Yeats, Russell turned to writing to supplement his income. Both Yeats and Russell shared a passion for theater, and founded the National Theatre Company. Russell wrote a play called “Deirdre,” designing the whimsical costumes worn in the first production. He lived at the Theosophical Society Lodge, and in true artist fashion painted murals across the walls of his home space. In the late 1890s, Russell was offered a job at the Irish Agricultural Organization Society, a co-operative founded by Horace Plunkett. Russell was a skilled organizer, travelling extensively throughout Ireland as a spokesman and developing credit societies. He was a proud nationalist who eventually became the editor of The Irish Homestead, which widened his influence as a gifted writer and publicist. Homestead gradually merged with The Irish Statesman, which Russell led as the editor for many years.

“A.E.” Russell lived in a house on Rathgar Avenue in Dublin, which became a kind of mecca for those interested in the economic and artistic future of Ireland. Poets, politicians, novelists, and mystics were drawn to this place in a spirit of kinship, with Russell offering counsel and an open door to all who came by. His hospitality, warm conversation, and selfless advice attracted innumerable guests including Jack Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Patrick Kavanaugh, Helen Waddell, Lady Gregory, P.L. Travers, and a young James Joyce. “A.E.” became a benevolent facilitator and ubiquitously respected mentor to generations of Irish writers.

Image is the front entrance of AE Russell’s former residence in Dublin, at 17 Rathgar Avenue

As the French writer Simone Tery famously summarized in “L’ile des Bards:”

“Do you want to know about providence, the origin of the universe, the end of the universe?

Go to A.E.

Do you want to know about Gaelic literature?

Go to A.E.

Do you want to know about the Celtic soul?

Go to A.E.

Do you want to know about Irish History?

Go to A.E.

Do you want to know about the export of eggs?

Go to A.E.

Do you want to know how to run society?

Go to A.E.

If you find life insipid -

Go to A.E.

If you need a friend -

Go to A.E.”

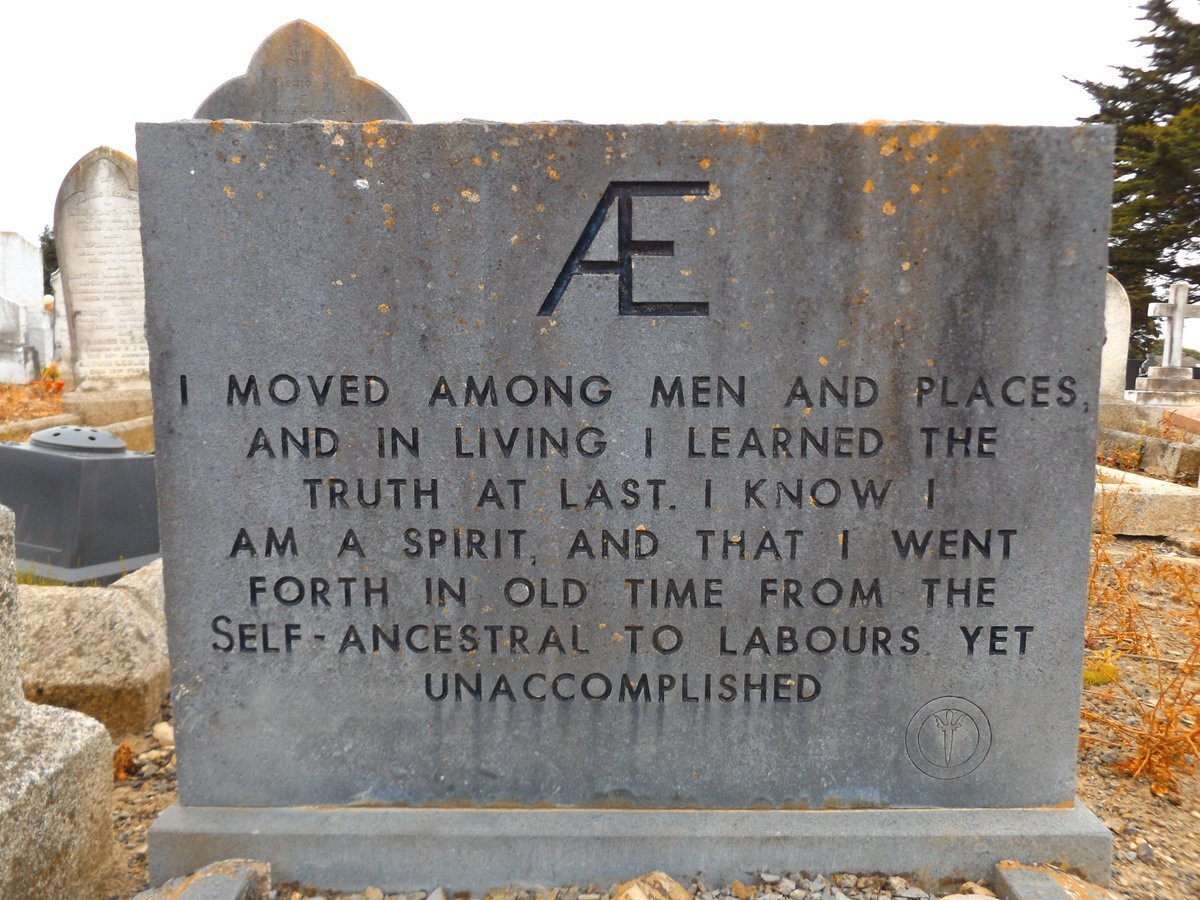

While Russell had continued to paint and publish his novels and poetry during his time as editor, he had not seen much revenue from those endeavors. When the newspaper closed in April of 1930, he was instantly concerned that he would find himself without a job for the first time in his life. Without his knowing, meetings were held and collections taken on his behalf. Friends and colleagues presented him with a large cheque that financed his ability to travel to America, where his work was well-received. After touring America, Russell returned home, and relocated to England after his wife’s passing in 1932. He died in Bournemouth just a few short years later, in 1935. It is said that P.L. Travers and Gogarty were at his bedside during his final days. “A.E.” was laid to rest in Mount Jerome Cemetery, in his native city of Dublin.

Epitaph of AE, the Gravesite of George William Russell (1867 - 1935)

AE Russell stands out to me as an exceptional Renaissance individual, eternally moved by the spirit quest that fueled his infinite interests with a desire to honor his cultural roots. A theosophist who wrote extensively on politics and economics, AE continued to paint and write poetry though all of his pursuits. His paintings illustrate a glowing landscape of imagination, inviting us in to his unique spirituality. Through the visual realm AE was able to best express himself as a mystic--he lifted inspiration from the natural world of his homeland and merged the outer vision with the inner sense. Many of his paintings have a consistent subject matter, as though he were searching through each one for another unexplored corner of a singular vision. He often left works untitled, which is why several of his paintings have various names. Many are held in private collections, but there are museums throughout Ireland where his work can be appreciated today. These include the Armagh County Museum, the Niland Gallery in Sligo, and the National Gallery in Dublin.

I certainly hope to travel there and see them in person someday.

Review and original sketches by Jessie Howe. March 4th, 2021

Paintings by ‘AE’ George William Russell:

AE exhibited his paintings in 1904. Here is an impression from one attendee, mused by a reputable chronicler named Joseph Holloway:

“But who could explain the beyond-the-world feelings and sense of restfulness that held the imagination as they gazed on those strange, mystic visions of beauty, conjured up by the poetic mind of a dreamer of the twilight kingdom inhabited by the children of the mist--the gossamer beings of the raths of Ireland.”

For further reading...

Biography:

That Myriad-Minded Man, by Henry Summerfield

Highlights of Works by AE:

Homeward: Songs by the Way (1894); his first published book of poems

The Earth Breath (1897)

Collected Poems, published during 1913, with a second edition during 1926.

Enchantment and Other Poems (1930)

Selected Poems (1935)

The Candle of Vision, (1918)

The Interpreters (1922), inscribed to Gogarty

Song and Its Fountains, (1932)

The Avatars (1933), dedicated to his lifelong friend W.B. Yeats

Have you read other works by AE Russell? If so, please share your thoughts and comment below!